Open to comments

05.12.2006Technorati tags: Bolivia politics political science

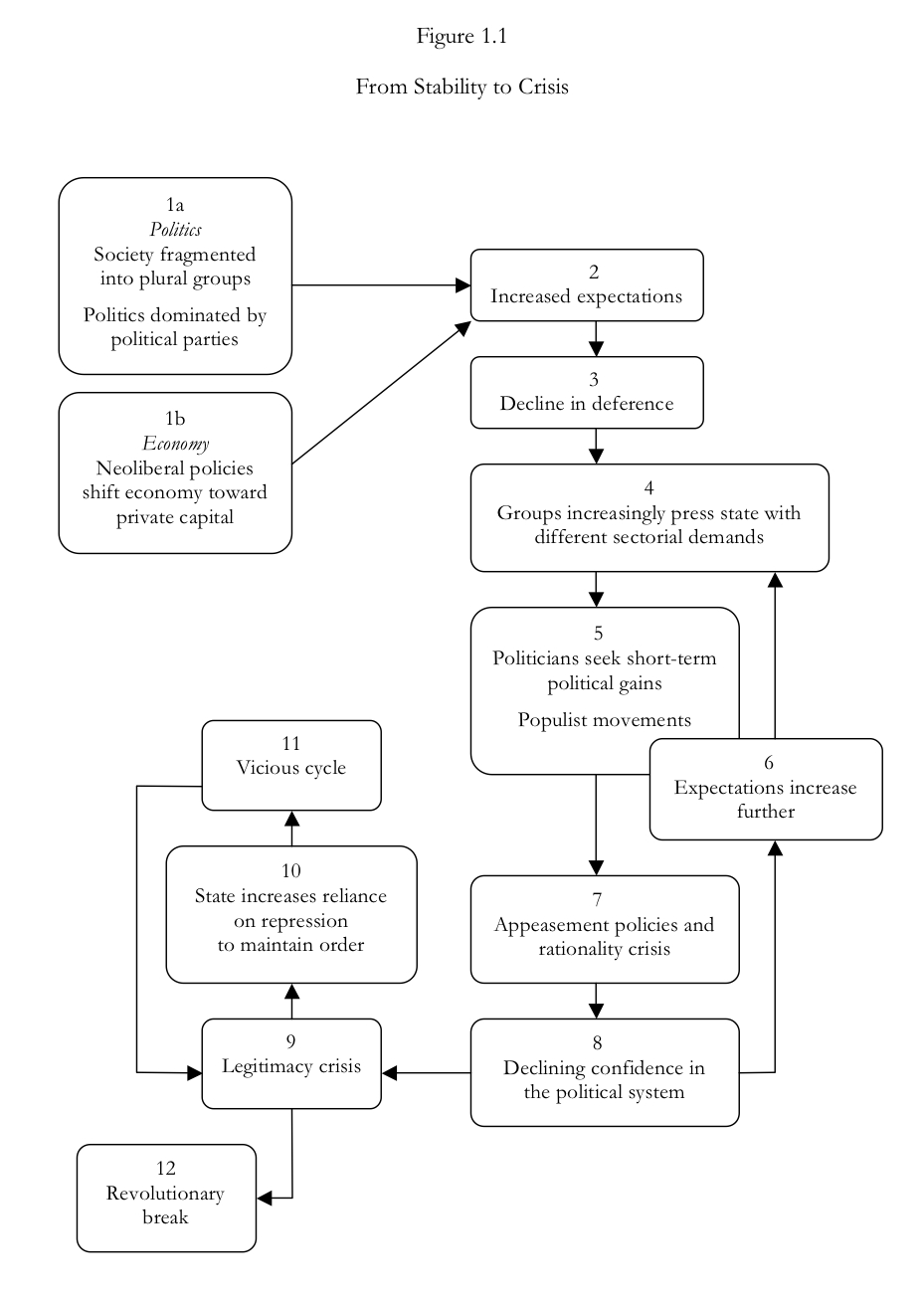

Below is a short section of the introduction to my dissertation & a flowchart meant to explain how Bolivia went from political stability (1985-2000), to a crisis of legitimacy (after 2000), to the October 2003 break. I'm opening it up to comments (especially from Bolivian & political science blogospheres) while I wait to hear from my committee. I think it does a decent job explaining not only the recent Bolivian experience, but also how other new democracies are susceptible to crisis from what I call "the paradox of democratization" (explained elsewhere in the chapter).

From Political Stability to Crisis of Legitimacy

This dissertation seeks to explain how Bolivia's nearly two decades of political stability gave way to a period of instability followed by a radical break that fundamentally altered the status quo. My model mirrors the model presented by David Held (1996) for explaining the social unrest in post-industrial liberal democracies in the 1960s (see pp. 233-253). While the Bolivian case is clearly different, many of the features described by theorists of "overloaded government" and theorists of "legitimation crisis" apply to the Bolivian case as well. In the place of the erosion of confidence in a post-industrial welfare state, my model looks at the erosion of confidence in a newly democratized regime consistent with the paradox of democratization. As such, I accept many of the pluralist premises of the overloaded government theorists, as well as the more radical critiques of liberal democracy’s ability to manage social and economic conflicts presented by the legitimation crisis theorists.

The key features of the argument are spelled out in Figure 1.1 and are briefly discussed below.

1a. Political power is fragmented among a plurality of groups (class, ethnic, regional, etc.) but is exercised by political parties. Though parties compete in the formal electoral arena, their power is constrained by economic realities. Still, the transition to democracy makes government more responsive to social demands.

1b. The economy is characterized by neoliberal policies, which involve dismantling the state's previous role in economic affairs and significant structural adjustments. Neoliberal reforms are at first successful in stabilizing the economy.

2. Expectation increase. Politically, individual and groups begin to expect an increase in freedoms and greater autonomy. Economically, the citizens expect greater prosperity to follow the transition to a free market economy.

3. Rising expectations are reinforced by a "decline in deference" consistent with a transition from authoritarianism to democracy.

4. A combination of increased expectations and declining deference leads groups to increasingly press the new democratic government to meet various sectorial (and often contradictory) demands.

5. In order to maximize their vote-winning potential, political elites adopt short-term strategies and promise more than they are able to deliver to their constituents. Electoral competition drives parties to continuously increase their promises. Populist parties also emerge, capitalizing on unmet expectations.

6. Thus, aspirations increase as voters continue to seek political alternatives that will meet their expectations. This leads groups to continue to press their sectorial demands upon government. This loop (steps 4-6) continues until the political system becomes overloaded.

7. Once demands increase beyond a certain point, political elites follow policies of "appeasement" as they scramble to incorporate as many different sectorial groups under their banner to maximize their vote-winning potential. Similarly, the state ceases to exercise its authority but instead engages in negotiations with sectorial groups that increasingly channel their demands into direct action, rather than the representative political process. Meanwhile, a "rationality crisis" ensues as the state becomes increasingly used as a means to distribute patronage (in efforts by elites to secure political support and governability).

8. The combination of an ineffective state and unmet (but increasing) expectations leads to a decline in confidence in the state and the political system — especially political parties.

9. If increasing demands cannot be met by available alternatives, the entire political system soon faces a crisis of legitimacy as calls for reform are replaced by calls for revolutionary change.

10. Increasingly under siege and facing a loss of public legitimacy among much of the population, the state eventually responds with repressive force in efforts to maintain political and economic stability.

11. This initiates a vicious cycle: The state continuously relies on repression to maintain public order in the face of increasingly aggressive public manifestations. This only heightens the legitimacy crisis.

12. The combination of continued decline in public confidence in the political system, continuously increasing demands, growing social unrest, and the state’s reliance on repression may lead to a revolutionary break. This is what happened in October 2003. During two decades, public confidence in the political system slowly eroded even as political elites continued to engage in short-term electoral calculations. Increasingly frequent violent social unrest and state repression — for example, the April 2000 Cochabamba "water war" and the 2003 impuestazo revolt — demonstrated a legitimacy crisis from 2000 onward.

Posted by Miguel at 01:37 PM

Comments

2. Expectation increase. Politically, individual and groups... (I believe that the word individual should be plural).

I enjoy reading your blog and also watching a young Bolivian make his place in the world of education.

Posted by: William J. Goodrich at May 15, 2006 07:15 PM

Thanks, especially for the typo. I went through numerous drafts, and somehow it ended up incorrect. I'll correct it right away.

Posted by: mcentellas ![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.centellas.org/miguel/nav-commenters.gif) at May 15, 2006 07:43 PM

at May 15, 2006 07:43 PM

Hi Miguel

Just to say a HUGE thank you for your enlightening articles. I volunteer for a Bolivian organization, but my Spanish is so slow these days I can't keep up with topical affairs. Your contributions are excellent - clearly a balanced, expert and compassionate viewpoint concisely conveyed - of huge value for me understanding a Bolivian organization and representing it for Westerners.

All the best with your marriage and studies,

Chris

Posted by: Chris Preager at May 16, 2006 12:02 PM